TCP models in ns-3¶

This chapter describes the TCP models available in ns-3.

Overview of support for TCP¶

ns-3 was written to support multiple TCP implementations. The implementations

inherit from a few common header classes in the src/network directory, so that

user code can swap out implementations with minimal changes to the scripts.

There are three important abstract base classes:

class

TcpSocket: This is defined insrc/internet/model/tcp-socket.{cc,h}. This class exists for hosting TcpSocket attributes that can be reused across different implementations. For instance, the attributeInitialCwndcan be used for any of the implementations that derive from classTcpSocket.class

TcpSocketFactory: This is used by the layer-4 protocol instance to create TCP sockets of the right type.class

TcpCongestionOps: This supports different variants of congestion control– a key topic of simulation-based TCP research.

There are presently two active implementations of TCP available for ns-3.

a natively implemented TCP for ns-3

support for kernel implementations via Direct Code Execution (DCE)

Direct Code Execution is limited in its support for newer kernels; at present, only Linux kernel 4.4 is supported. However, the TCP implementations in kernel 4.4 can still be used for ns-3 validation or for specialized simulation use cases.

It should also be mentioned that various ways of combining virtual machines with ns-3 makes available also some additional TCP implementations, but those are out of scope for this chapter.

ns-3 TCP¶

In brief, the native ns-3 TCP model supports a full bidirectional TCP with connection setup and close logic. Several congestion control algorithms are supported, with CUBIC the default, and NewReno, Westwood, Hybla, HighSpeed, Vegas, Scalable, Veno, Binary Increase Congestion Control (BIC), Yet Another HighSpeed TCP (YeAH), Illinois, H-TCP, Low Extra Delay Background Transport (LEDBAT), TCP Low Priority (TCP-LP), Data Center TCP (DCTCP) and Bottleneck Bandwidth and RTT (BBR) also supported. The model also supports Selective Acknowledgements (SACK), Proportional Rate Reduction (PRR) and Explicit Congestion Notification (ECN). Multipath-TCP is not yet supported in the ns-3 releases.

Model history¶

Until the ns-3.10 release, ns-3 contained a port of the TCP model from GTNetS, developed initially by George Riley and ported to ns-3 by Raj Bhattacharjea. This implementation was substantially rewritten by Adriam Tam for ns-3.10. In 2015, the TCP module was redesigned in order to create a better environment for creating and carrying out automated tests. One of the main changes involves congestion control algorithms, and how they are implemented.

Before the ns-3.25 release, a congestion control was considered as a stand-alone TCP

through an inheritance relation: each congestion control (e.g. TcpNewReno) was

a subclass of TcpSocketBase, reimplementing some inherited methods. The

architecture was redone to avoid this inheritance,

by making each congestion control a separate class, and defining an interface

to exchange important data between TcpSocketBase and the congestion modules.

The Linux tcp_congestion_ops interface was used as the design reference.

Along with congestion control, Fast Retransmit and Fast Recovery algorithms have been modified; in previous releases, these algorithms were delegated to TcpSocketBase subclasses. Starting from ns-3.25, they have been merged inside TcpSocketBase. In future releases, they can be extracted as separate modules, following the congestion control design.

As of the ns-3.31 release, the default initial window was set to 10 segments (in previous releases, it was set to 1 segment). This aligns with current Linux default, and is discussed further in RFC 6928.

In the ns-3.32 release, the default recovery algorithm was set to Proportional Rate Reduction (PRR) from the classic ack-clocked Fast Recovery algorithm.

In the ns-3.34 release, the default congestion control algorithm was set to CUBIC from NewReno.

Acknowledgments¶

As mentioned above, ns-3 TCP has had multiple authors and maintainers over the years. Several publications exist on aspects of ns-3 TCP, and users of ns-3 TCP are requested to cite one of the applicable papers when publishing new work.

A general reference on the current architecture is found in the following paper:

Maurizio Casoni, Natale Patriciello, Next-generation TCP for ns-3 simulator, Simulation Modelling Practice and Theory, Volume 66, 2016, Pages 81-93. (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1569190X15300939)

For an academic peer-reviewed paper on the SACK implementation in ns-3, please refer to:

Natale Patriciello. 2017. A SACK-based Conservative Loss Recovery Algorithm for ns-3 TCP: a Linux-inspired Proposal. In Proceedings of the Workshop on ns-3 (WNS3 ‘17). ACM, New York, NY, USA, 1-8. (https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=3067666)

Usage¶

In many cases, usage of TCP is set at the application layer by telling the ns-3 application which kind of socket factory to use.

Using the helper functions defined in src/applications/helper and

src/network/helper, here is how one would create a TCP receiver:

// Create a packet sink on the star "hub" to receive these packets

uint16_t port = 50000;

Address sinkLocalAddress(InetSocketAddress (Ipv4Address::GetAny (), port));

PacketSinkHelper sinkHelper ("ns3::TcpSocketFactory", sinkLocalAddress);

ApplicationContainer sinkApp = sinkHelper.Install (serverNode);

sinkApp.Start (Seconds (1.0));

sinkApp.Stop (Seconds (10.0));

Similarly, the below snippet configures OnOffApplication traffic source to use TCP:

// Create the OnOff applications to send TCP to the server

OnOffHelper clientHelper ("ns3::TcpSocketFactory", Address ());

The careful reader will note above that we have specified the TypeId of an

abstract base class TcpSocketFactory. How does the script tell

ns-3 that it wants the native ns-3 TCP vs. some other one? Well, when

internet stacks are added to the node, the default TCP implementation that is

aggregated to the node is the ns-3 TCP. So, by default, when using the ns-3

helper API, the TCP that is aggregated to nodes with an Internet stack is the

native ns-3 TCP.

To configure behavior of TCP, a number of parameters are exported through the

ns-3 attribute system. These are documented in the Doxygen for class

TcpSocket. For example, the maximum segment size is a

settable attribute.

To set the default socket type before any internet stack-related objects are created, one may put the following statement at the top of the simulation program:

Config::SetDefault ("ns3::TcpL4Protocol::SocketType", StringValue ("ns3::TcpNewReno"));

For users who wish to have a pointer to the actual socket (so that

socket operations like Bind(), setting socket options, etc. can be

done on a per-socket basis), Tcp sockets can be created by using the

Socket::CreateSocket() method. The TypeId passed to CreateSocket()

must be of type ns3::SocketFactory, so configuring the underlying

socket type must be done by twiddling the attribute associated with the

underlying TcpL4Protocol object. The easiest way to get at this would be

through the attribute configuration system. In the below example,

the Node container “n0n1” is accessed to get the zeroth element, and a socket is

created on this node:

// Create and bind the socket...

TypeId tid = TypeId::LookupByName ("ns3::TcpNewReno");

Config::Set ("/NodeList/*/$ns3::TcpL4Protocol/SocketType", TypeIdValue (tid));

Ptr<Socket> localSocket =

Socket::CreateSocket (n0n1.Get (0), TcpSocketFactory::GetTypeId ());

Above, the “*” wild card for node number is passed to the attribute configuration system, so that all future sockets on all nodes are set to NewReno, not just on node ‘n0n1.Get (0)’. If one wants to limit it to just the specified node, one would have to do something like:

// Create and bind the socket...

TypeId tid = TypeId::LookupByName ("ns3::TcpNewReno");

std::stringstream nodeId;

nodeId << n0n1.Get (0)->GetId ();

std::string specificNode = "/NodeList/" + nodeId.str () + "/$ns3::TcpL4Protocol/SocketType";

Config::Set (specificNode, TypeIdValue (tid));

Ptr<Socket> localSocket =

Socket::CreateSocket (n0n1.Get (0), TcpSocketFactory::GetTypeId ());

Once a TCP socket is created, one will want to follow conventional socket logic and either connect() and send() (for a TCP client) or bind(), listen(), and accept() (for a TCP server). Please note that applications usually create the sockets they use automatically, and so is not straightforward to connect directly to them using pointers. Please refer to the source code of your preferred application to discover how and when it creates the socket.

TCP Socket interaction and interface with Application layer¶

In the following there is an analysis on the public interface of the TCP socket, and how it can be used to interact with the socket itself. An analysis of the callback fired by the socket is also carried out. Please note that, for the sake of clarity, we will use the terminology “Sender” and “Receiver” to clearly divide the functionality of the socket. However, in TCP these two roles can be applied at the same time (i.e. a socket could be a sender and a receiver at the same time): our distinction does not lose generality, since the following definition can be applied to both sockets in case of full-duplex mode.

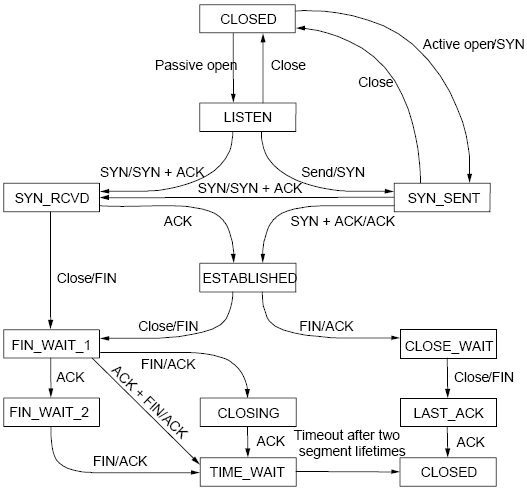

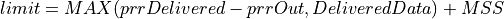

TCP state machine (for commodity use)

TCP State machine¶

In ns-3 we are fully compliant with the state machine depicted in Figure TCP State machine.

Public interface for receivers (e.g. servers receiving data)

- Bind()

Bind the socket to an address, or to a general endpoint. A general endpoint is an endpoint with an ephemeral port allocation (that is, a random port allocation) on the 0.0.0.0 IP address. For instance, in current applications, data senders usually binds automatically after a Connect() over a random port. Consequently, the connection will start from this random port towards the well-defined port of the receiver. The IP 0.0.0.0 is then translated by lower layers into the real IP of the device.

- Bind6()

Same as Bind(), but for IPv6.

- BindToNetDevice()

Bind the socket to the specified NetDevice, creating a general endpoint.

- Listen()

Listen on the endpoint for an incoming connection. Please note that this function can be called only in the TCP CLOSED state, and transit in the LISTEN state. When an incoming request for connection is detected (i.e. the other peer invoked Connect()) the application will be signaled with the callback NotifyConnectionRequest (set in SetAcceptCallback() beforehand). If the connection is accepted (the default behavior, when the associated callback is a null one) the Socket will fork itself, i.e. a new socket is created to handle the incoming data/connection, in the state SYN_RCVD. Please note that this newly created socket is not connected anymore to the callbacks on the “father” socket (e.g. DataSent, Recv); the pointer of the newly created socket is provided in the Callback NotifyNewConnectionCreated (set beforehand in SetAcceptCallback), and should be used to connect new callbacks to interesting events (e.g. Recv callback). After receiving the ACK of the SYN-ACK, the socket will set the congestion control, move into ESTABLISHED state, and then notify the application with NotifyNewConnectionCreated.

- ShutdownSend()

Signal a termination of send, or in other words prevents data from being added to the buffer. After this call, if buffer is already empty, the socket will send a FIN, otherwise FIN will go when buffer empties. Please note that this is useful only for modeling “Sink” applications. If you have data to transmit, please refer to the Send() / Close() combination of API.

- GetRxAvailable()

Get the amount of data that could be returned by the Socket in one or multiple call to Recv or RecvFrom. Please use the Attribute system to configure the maximum available space on the receiver buffer (property “RcvBufSize”).

- Recv()

Grab data from the TCP socket. Please remember that TCP is a stream socket, and it is allowed to concatenate multiple packets into bigger ones. If no data is present (i.e. GetRxAvailable returns 0) an empty packet is returned. Set the callback RecvCallback through SetRecvCallback() in order to have the application automatically notified when some data is ready to be read. It’s important to connect that callback to the newly created socket in case of forks.

- RecvFrom()

Same as Recv, but with the source address as parameter.

Public interface for senders (e.g. clients uploading data)

- Connect()

Set the remote endpoint, and try to connect to it. The local endpoint should be set before this call, or otherwise an ephemeral one will be created. The TCP then will be in the SYN_SENT state. If a SYN-ACK is received, the TCP will setup the congestion control, and then call the callback ConnectionSucceeded.

- GetTxAvailable()

Return the amount of data that can be stored in the TCP Tx buffer. Set this property through the Attribute system (“SndBufSize”).

- Send()

Send the data into the TCP Tx buffer. From there, the TCP rules will decide if, and when, this data will be transmitted. Please note that, if the tx buffer has enough data to fill the congestion (or the receiver) window, dynamically varying the rate at which data is injected in the TCP buffer does not have any noticeable effect on the amount of data transmitted on the wire, that will continue to be decided by the TCP rules.

- SendTo()

Same as Send().

- Close()

Terminate the local side of the connection, by sending a FIN (after all data in the tx buffer has been transmitted). This does not prevent the socket in receiving data, and employing retransmit mechanism if losses are detected. If the application calls Close() with unread data in its rx buffer, the socket will send a reset. If the socket is in the state SYN_SENT, CLOSING, LISTEN, FIN_WAIT_2, or LAST_ACK, after that call the application will be notified with NotifyNormalClose(). In other cases, the notification is delayed (see NotifyNormalClose()).

Public callbacks

These callbacks are called by the TCP socket to notify the application of interesting events. We will refer to these with the protected name used in socket.h, but we will provide the API function to set the pointers to these callback as well.

- NotifyConnectionSucceeded: SetConnectCallback, 1st argument

Called in the SYN_SENT state, before moving to ESTABLISHED. In other words, we have sent the SYN, and we received the SYN-ACK: the socket prepares the sequence numbers, sends the ACK for the SYN-ACK, tries to send out more data (in another segment) and then invokes this callback. After this callback, it invokes the NotifySend callback.

- NotifyConnectionFailed: SetConnectCallback, 2nd argument

Called after the SYN retransmission count goes to 0. SYN packet is lost multiple times, and the socket gives up.

- NotifyNormalClose: SetCloseCallbacks, 1st argument

A normal close is invoked. A rare case is when we receive an RST segment (or a segment with bad flags) in normal states. All other cases are: - The application tries to Connect() over an already connected socket - Received an ACK for the FIN sent, with or without the FIN bit set (we are in LAST_ACK) - The socket reaches the maximum amount of retries in retransmitting the SYN (*) - We receive a timeout in the LAST_ACK state - Upon entering the TIME_WAIT state, before waiting the 2*Maximum Segment Lifetime seconds to finally deallocate the socket.

- NotifyErrorClose: SetCloseCallbacks, 2nd argument

Invoked when we send an RST segment (for whatever reason) or we reached the maximum amount of data retries.

- NotifyConnectionRequest: SetAcceptCallback, 1st argument

Invoked in the LISTEN state, when we receive a SYN. The return value indicates if the socket should accept the connection (return true) or should ignore it (return false).

- NotifyNewConnectionCreated: SetAcceptCallback, 2nd argument

Invoked when from SYN_RCVD the socket passes to ESTABLISHED, and after setting up the congestion control, the sequence numbers, and processing the incoming ACK. If there is some space in the buffer, NotifySend is called shortly after this callback. The Socket pointer, passed with this callback, is the newly created socket, after a Fork().

- NotifyDataSent: SetDataSentCallback

The Socket notifies the application that some bytes have been transmitted on the IP level. These bytes could still be lost in the node (traffic control layer) or in the network.

- NotifySend: SetSendCallback

Invoked if there is some space in the tx buffer when entering the ESTABLISHED state (e.g. after the ACK for SYN-ACK is received), after the connection succeeds (e.g. after the SYN-ACK is received) and after each new ACK (i.e. that advances SND.UNA).

- NotifyDataRecv: SetRecvCallback

Called when in the receiver buffer there are in-order bytes, and when in FIN_WAIT_1 or FIN_WAIT_2 the socket receive a in-sequence FIN (that can carry data).

Congestion Control Algorithms¶

Here follows a list of supported TCP congestion control algorithms. For an academic paper on many of these congestion control algorithms, see http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2756518 .

NewReno¶

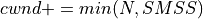

NewReno algorithm introduces partial ACKs inside the well-established Reno algorithm. This and other modifications are described in RFC 6582. We have two possible congestion window increment strategy: slow start and congestion avoidance. Taken from RFC 5681:

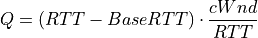

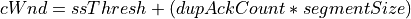

During slow start, a TCP increments cwnd by at most SMSS bytes for each ACK received that cumulatively acknowledges new data. Slow start ends when cwnd exceeds ssthresh (or, optionally, when it reaches it, as noted above) or when congestion is observed. While traditionally TCP implementations have increased cwnd by precisely SMSS bytes upon receipt of an ACK covering new data, we RECOMMEND that TCP implementations increase cwnd, per Equation (1), where N is the number of previously unacknowledged bytes acknowledged in the incoming ACK.

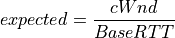

(1)¶

During congestion avoidance, cwnd is incremented by roughly 1 full-sized segment per round-trip time (RTT), and for each congestion event, the slow start threshold is halved.

CUBIC¶

CUBIC (class TcpCubic) is the default TCP congestion control

in Linux, macOS (since 2014), and Microsoft Windows (since 2017).

CUBIC has two main differences with respect to

a more classic TCP congestion control such as NewReno. First, during the

congestion avoidance phase, the window size grows according to a cubic

function (concave, then convex) with the latter convex portion designed

to allow for bandwidth probing. Second, a hybrid slow start (HyStart)

algorithm uses observations of delay increases in the slow start

phase of window growth to try to exit slow start before window growth

causes queue overflow.

CUBIC is documented in RFC 8312, and the ns-3 implementation is based on the RFC more so than the Linux implementation, although the Linux 4.4 kernel implementation (through the Direct Code Execution environment) has been used to validate the behavior and is fairly well aligned (see below section on validation).

Linux Reno¶

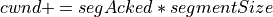

TCP Linux Reno (class TcpLinuxReno) is designed to provide a

Linux-like implementation of

TCP NewReno. The implementation of class TcpNewReno in ns-3

follows RFC standards, and increases cwnd more conservatively than does Linux Reno.

Linux Reno modifies slow start and congestion avoidance algorithms to

increase cwnd based on the number of bytes being acknowledged by each

arriving ACK, rather than by the number of ACKs that arrive. Another major

difference in implementation is that Linux maintains the congestion window

in units of segments, while the RFCs define the congestion window in units of

bytes.

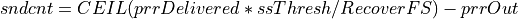

In slow start phase, on each incoming ACK at the TCP sender side cwnd is increased by the number of previously unacknowledged bytes ACKed by the incoming acknowledgment. In contrast, in ns-3 NewReno, cwnd is increased by one segment per acknowledgment. In standards terminology, this difference is referred to as Appropriate Byte Counting (RFC 3465); Linux follows Appropriate Byte Counting while ns-3 NewReno does not.

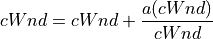

(2)¶

(3)¶

In congestion avoidance phase, the number of bytes that have been ACKed at the TCP sender side are stored in a ‘bytes_acked’ variable in the TCP control block. When ‘bytes_acked’ becomes greater than or equal to the value of the cwnd, ‘bytes_acked’ is reduced by the value of cwnd. Next, cwnd is incremented by a full-sized segment (SMSS). In contrast, in ns-3 NewReno, cwnd is increased by (1/cwnd) with a rounding off due to type casting into int.

if (m_cWndCnt >= w)

{

uint32_t delta = m_cWndCnt / w;

m_cWndCnt -= delta * w;

tcb->m_cWnd += delta * tcb->m_segmentSize;

NS_LOG_DEBUG ("Subtracting delta * w from m_cWndCnt " << delta * w);

}

:label: linuxrenocongavoid

if (segmentsAcked > 0)

{

double adder = static_cast<double> (tcb->m_segmentSize * tcb->m_segmentSize) / tcb->m_cWnd.Get ();

adder = std::max (1.0, adder);

tcb->m_cWnd += static_cast<uint32_t> (adder);

NS_LOG_INFO ("In CongAvoid, updated to cwnd " << tcb->m_cWnd <<

" ssthresh " << tcb->m_ssThresh);

}

:label: newrenocongavoid

So, there are two main difference between the TCP Linux Reno and TCP NewReno in ns-3: 1) In TCP Linux Reno, delayed acknowledgement configuration does not affect congestion window growth, while in TCP NewReno, delayed acknowledgments cause a slower congestion window growth. 2) In congestion avoidance phase, the arithmetic for counting the number of segments acked and deciding when to increment the cwnd is different for TCP Linux Reno and TCP NewReno.

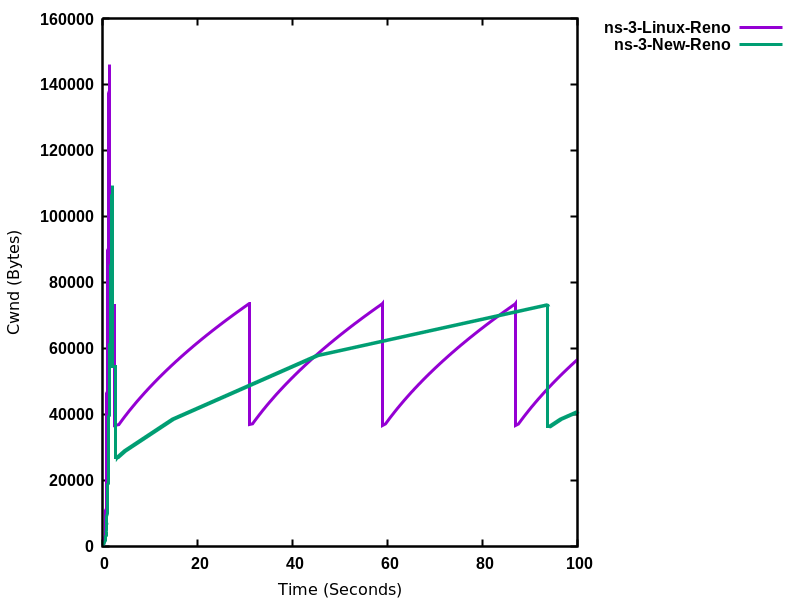

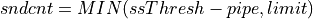

Following graphs shows the behavior of window growth in TCP Linux Reno and TCP NewReno with delayed acknowledgement of 2 segments:

ns-3 TCP NewReno vs. ns-3 TCP Linux Reno¶

HighSpeed¶

TCP HighSpeed is designed for high-capacity channels or, in general, for TCP connections with large congestion windows. Conceptually, with respect to the standard TCP, HighSpeed makes the cWnd grow faster during the probing phases and accelerates the cWnd recovery from losses. This behavior is executed only when the window grows beyond a certain threshold, which allows TCP HighSpeed to be friendly with standard TCP in environments with heavy congestion, without introducing new dangers of congestion collapse.

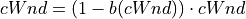

Mathematically:

(4)¶

The function a() is calculated using a fixed RTT the value 100 ms (the lookup table for this function is taken from RFC 3649). For each congestion event, the slow start threshold is decreased by a value that depends on the size of the slow start threshold itself. Then, the congestion window is set to such value.

(5)¶

The lookup table for the function b() is taken from the same RFC. More information at: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2756518

Hybla¶

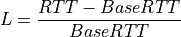

The key idea behind TCP Hybla is to obtain for long RTT connections the same instantaneous transmission rate of a reference TCP connection with lower RTT. With analytical steps, it is shown that this goal can be achieved by modifying the time scale, in order for the throughput to be independent from the RTT. This independence is obtained through the use of a coefficient rho.

This coefficient is used to calculate both the slow start threshold and the congestion window when in slow start and in congestion avoidance, respectively.

More information at: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2756518

Westwood¶

Westwood and Westwood+ employ the AIAD (Additive Increase/Adaptive Decrease) congestion control paradigm. When a congestion episode happens, instead of halving the cwnd, these protocols try to estimate the network’s bandwidth and use the estimated value to adjust the cwnd. While Westwood performs the bandwidth sampling every ACK reception, Westwood+ samples the bandwidth every RTT.

WARNING: this TCP model lacks validation and regression tests; use with caution.

More information at: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=381704 and http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2512757

Vegas¶

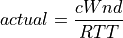

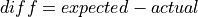

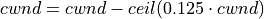

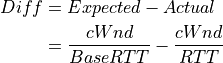

TCP Vegas is a pure delay-based congestion control algorithm implementing a proactive scheme that tries to prevent packet drops by maintaining a small backlog at the bottleneck queue. Vegas continuously samples the RTT and computes the actual throughput a connection achieves using Equation (6) and compares it with the expected throughput calculated in Equation (7). The difference between these 2 sending rates in Equation (8) reflects the amount of extra packets being queued at the bottleneck.

(6)¶

(7)¶

(8)¶

To avoid congestion, Vegas linearly increases/decreases its congestion window to ensure the diff value falls between the two predefined thresholds, alpha and beta. diff and another threshold, gamma, are used to determine when Vegas should change from its slow-start mode to linear increase/decrease mode. Following the implementation of Vegas in Linux, we use 2, 4, and 1 as the default values of alpha, beta, and gamma, respectively, but they can be modified through the Attribute system.

More information at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/49.464716

Scalable¶

Scalable improves TCP performance to better utilize the available bandwidth of a highspeed wide area network by altering NewReno congestion window adjustment algorithm. When congestion has not been detected, for each ACK received in an RTT, Scalable increases its cwnd per:

(9)¶

Following Linux implementation of Scalable, we use 50 instead of 100 to account for delayed ACK.

On the first detection of congestion in a given RTT, cwnd is reduced based on the following equation:

(10)¶

More information at: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=956989

Veno¶

TCP Veno enhances Reno algorithm for more effectively dealing with random packet loss in wireless access networks by employing Vegas’s method in estimating the backlog at the bottleneck queue to distinguish between congestive and non-congestive states.

The backlog (the number of packets accumulated at the bottleneck queue) is calculated using Equation (11):

(11)¶

where:

(12)¶

Veno makes decision on cwnd modification based on the calculated N and its predefined threshold beta.

Specifically, it refines the additive increase algorithm of Reno so that the connection can stay longer in the stable state by incrementing cwnd by 1/cwnd for every other new ACK received after the available bandwidth has been fully utilized, i.e. when N exceeds beta. Otherwise, Veno increases its cwnd by 1/cwnd upon every new ACK receipt as in Reno.

In the multiplicative decrease algorithm, when Veno is in the non-congestive state, i.e. when N is less than beta, Veno decrements its cwnd by only 1/5 because the loss encountered is more likely a corruption-based loss than a congestion-based. Only when N is greater than beta, Veno halves its sending rate as in Reno.

More information at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/JSAC.2002.807336

BIC¶

BIC (class TcpBic) is a predecessor of TCP CUBIC.

In TCP BIC the congestion control problem is viewed as a search

problem. Taking as a starting point the current window value

and as a target point the last maximum window value

(i.e. the cWnd value just before the loss event) a binary search

technique can be used to update the cWnd value at the midpoint between

the two, directly or using an additive increase strategy if the distance from

the current window is too large.

This way, assuming a no-loss period, the congestion window logarithmically approaches the maximum value of cWnd until the difference between it and cWnd falls below a preset threshold. After reaching such a value (or the maximum window is unknown, i.e. the binary search does not start at all) the algorithm switches to probing the new maximum window with a ‘slow start’ strategy.

If a loss occur in either these phases, the current window (before the loss) can be treated as the new maximum, and the reduced (with a multiplicative decrease factor Beta) window size can be used as the new minimum.

More information at: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/xpl/articleDetails.jsp?arnumber=1354672

YeAH¶

YeAH-TCP (Yet Another HighSpeed TCP) is a heuristic designed to balance various requirements of a state-of-the-art congestion control algorithm:

fully exploit the link capacity of high BDP networks while inducing a small number of congestion events

compete friendly with Reno flows

achieve intra and RTT fairness

robust to random losses

achieve high performance regardless of buffer size

YeAH operates between 2 modes: Fast and Slow mode. In the Fast mode when the queue occupancy is small and the network congestion level is low, YeAH increments its congestion window according to the aggressive HSTCP rule. When the number of packets in the queue grows beyond a threshold and the network congestion level is high, YeAH enters its Slow mode, acting as Reno with a decongestion algorithm. YeAH employs Vegas’ mechanism for calculating the backlog as in Equation (13). The estimation of the network congestion level is shown in Equation (14).

(13)¶

(14)¶

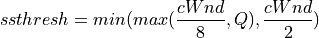

To ensure TCP friendliness, YeAH also implements an algorithm to detect the presence of legacy Reno flows. Upon the receipt of 3 duplicate ACKs, YeAH decreases its slow start threshold according to Equation (15) if it’s not competing with Reno flows. Otherwise, the ssthresh is halved as in Reno:

(15)¶

More information: http://www.csc.lsu.edu/~sjpark/cs7601/4-YeAH_TCP.pdf

Illinois¶

TCP Illinois is a hybrid congestion control algorithm designed for high-speed networks. Illinois implements a Concave-AIMD (or C-AIMD) algorithm that uses packet loss as the primary congestion signal to determine the direction of window update and queueing delay as the secondary congestion signal to determine the amount of change.

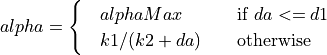

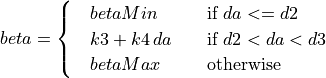

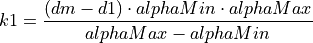

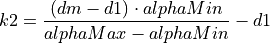

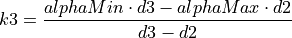

The additive increase and multiplicative decrease factors (denoted as alpha and beta, respectively) are functions of the current average queueing delay da as shown in Equations (16) and (17). To improve the protocol robustness against sudden fluctuations in its delay sampling, Illinois allows the increment of alpha to alphaMax only if da stays below d1 for a some (theta) amount of time.

(16)¶

(17)¶

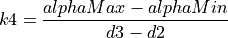

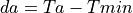

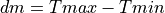

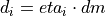

where the calculations of k1, k2, k3, and k4 are shown in the following:

(18)¶

(19)¶

(20)¶

(21)¶

Other parameters include da (the current average queueing delay), and Ta (the average RTT, calculated as sumRtt / cntRtt in the implementation) and Tmin (baseRtt in the implementation) which is the minimum RTT ever seen. dm is the maximum (average) queueing delay, and Tmax (maxRtt in the implementation) is the maximum RTT ever seen.

(22)¶

(23)¶

(24)¶

Illinois only executes its adaptation of alpha and beta when cwnd exceeds a threshold called winThresh. Otherwise, it sets alpha and beta to the base values of 1 and 0.5, respectively.

Following the implementation of Illinois in the Linux kernel, we use the following default parameter settings:

alphaMin = 0.3 (0.1 in the Illinois paper)

alphaMax = 10.0

betaMin = 0.125

betaMax = 0.5

winThresh = 15 (10 in the Illinois paper)

theta = 5

eta1 = 0.01

eta2 = 0.1

eta3 = 0.8

More information: http://www.doi.org/10.1145/1190095.1190166

H-TCP¶

H-TCP has been designed for high BDP (Bandwidth-Delay Product) paths. It is

a dual mode protocol. In normal conditions, it works like traditional TCP

with the same rate of increment and decrement for the congestion window.

However, in high BDP networks, when it finds no congestion on the path

after deltal seconds, it increases the window size based on the alpha

function in the following:

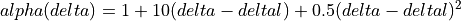

(25)¶

where deltal is a threshold in seconds for switching between the modes and

delta is the elapsed time from the last congestion. During congestion,

it reduces the window size by multiplying by beta function provided

in the reference paper. The calculated throughput between the last two

consecutive congestion events is considered for beta calculation.

The transport TcpHtcp can be selected in the program

examples/tcp/tcp-variants-comparison.cc to perform an experiment with H-TCP,

although it is useful to increase the bandwidth in this example (e.g.

to 20 Mb/s) to create a higher BDP link, such as

./ns3 run "tcp-variants-comparison --transport_prot=TcpHtcp --bandwidth=20Mbps --duration=10"

More information (paper): http://www.hamilton.ie/net/htcp3.pdf

More information (Internet Draft): https://tools.ietf.org/html/draft-leith-tcp-htcp-06

LEDBAT¶

Low Extra Delay Background Transport (LEDBAT) is an experimental delay-based congestion control algorithm that seeks to utilize the available bandwidth on an end-to-end path while limiting the consequent increase in queueing delay on that path. LEDBAT uses changes in one-way delay measurements to limit congestion that the flow itself induces in the network.

As a first approximation, the LEDBAT sender operates as shown below:

On receipt of an ACK:

- ::

currentdelay = acknowledgement.delay basedelay = min (basedelay, currentdelay) queuingdelay = currentdelay - basedelay offtarget = (TARGET - queuingdelay) / TARGET cWnd += GAIN * offtarget * bytesnewlyacked * MSS / cWnd

TARGET is the maximum queueing delay that LEDBAT itself may introduce in the

network, and GAIN determines the rate at which the cwnd responds to changes in

queueing delay; offtarget is a normalized value representing the difference between

the measured current queueing delay and the predetermined TARGET delay. offtarget can

be positive or negative; consequently, cwnd increases or decreases in proportion to

offtarget.

Following the recommendation of RFC 6817, the default values of the parameters are:

TargetDelay = 100

baseHistoryLen = 10

noiseFilterLen = 4

Gain = 1

To enable LEDBAT on all TCP sockets, the following configuration can be used:

Config::SetDefault ("ns3::TcpL4Protocol::SocketType", TypeIdValue (TcpLedbat::GetTypeId ()));

To enable LEDBAT on a chosen TCP socket, the following configuration can be used:

Config::Set ("$ns3::NodeListPriv/NodeList/1/$ns3::TcpL4Protocol/SocketType", TypeIdValue (TcpLedbat::GetTypeId ()));

The following unit tests have been written to validate the implementation of LEDBAT:

LEDBAT should operate same as NewReno during slow start

LEDBAT should operate same as NewReno if timestamps are disabled

Test to validate cwnd increment in LEDBAT

In comparison to RFC 6817, the scope and limitations of the current LEDBAT implementation are:

It assumes that the clocks on the sender side and receiver side are synchronised

In line with Linux implementation, the one-way delay is calculated at the sender side by using the timestamps option in TCP header

Only the MIN function is used for noise filtering

More information about LEDBAT is available in RFC 6817: https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc6817

TCP-LP¶

TCP-Low Priority (TCP-LP) is a delay based congestion control protocol in which the low priority data utilizes only the excess bandwidth available on an end-to-end path. TCP-LP uses one way delay measurements as an indicator of congestion as it does not influence cross-traffic in the reverse direction.

On receipt of an ACK:

where owdMin and owdMax are the minimum and maximum one way delays experienced throughout the connection, LP_WITHIN_INF indicates if TCP-LP is in inference phase or not

More information (paper): http://cs.northwestern.edu/~akuzma/rice/doc/TCP-LP.pdf

Data Center TCP (DCTCP)¶

DCTCP, specified in RFC 8257 and implemented in Linux, is a TCP congestion control algorithm for data center networks. It leverages Explicit Congestion Notification (ECN) to provide more fine-grained congestion feedback to the end hosts, and is intended to work with routers that implement a shallow congestion marking threshold (on the order of a few milliseconds) to achieve high throughput and low latency in the datacenter. However, because DCTCP does not react in the same way to notification of congestion experienced, there are coexistence (fairness) issues between it and legacy TCP congestion controllers, which is why it is recommended to only be used in controlled networking environments such as within data centers.

DCTCP extends the Explicit Congestion Notification signal to estimate the fraction of bytes that encounter congestion, rather than simply detecting that the congestion has occurred. DCTCP then scales the congestion window based on this estimate. This approach achieves high burst tolerance, low latency, and high throughput with shallow-buffered switches.

Receiver functionality: If CE is observed in the IP header of an incoming packet at the TCP receiver, the receiver sends congestion notification to the sender by setting ECE in TCP header. This processing is different from standard receiver ECN processing which sets and holds the ECE bit for every ACK until it observes a CWR signal from the TCP sender.

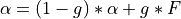

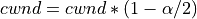

Sender functionality: The sender makes use of the modified receiver ECE semantics to maintain an estimate of the fraction of packets marked (

) by using the exponential weighted moving average (EWMA) as

shown below:

) by using the exponential weighted moving average (EWMA) as

shown below:

In the above EWMA:

g is the estimation gain (between 0 and 1)

F is the fraction of packets marked in current RTT.

For send windows in which at least one ACK was received with ECE set, the sender should respond by reducing the congestion window as follows, once for every window of data:

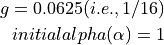

Following the recommendation of RFC 8257, the default values of the parameters are:

To enable DCTCP on all TCP sockets, the following configuration can be used:

Config::SetDefault ("ns3::TcpL4Protocol::SocketType", TypeIdValue (TcpDctcp::GetTypeId ()));

To enable DCTCP on a selected node, one can set the “SocketType” attribute on the TcpL4Protocol object of that node to the TcpDctcp TypeId.

The ECN is enabled automatically when DCTCP is used, even if the user has not explicitly enabled it.

DCTCP depends on a simple queue management algorithm in routers / switches to mark packets. The current implementation of DCTCP in ns-3 can use RED with a simple configuration to achieve the behavior of desired queue management algorithm.

To configure RED router for DCTCP:

Config::SetDefault ("ns3::RedQueueDisc::UseEcn", BooleanValue (true));

Config::SetDefault ("ns3::RedQueueDisc::QW", DoubleValue (1.0));

Config::SetDefault ("ns3::RedQueueDisc::MinTh", DoubleValue (16));

Config::SetDefault ("ns3::RedQueueDisc::MaxTh", DoubleValue (16));

There is also the option, when running CoDel or FqCoDel, to enable ECN on the queue and to set the “CeThreshold” value to a low value such as 1ms. The following example uses CoDel:

Config::SetDefault ("ns3::CoDelQueueDisc::UseEcn", BooleanValue (true));

Config::SetDefault ("ns3::CoDelQueueDisc::CeThreshold", TimeValue (MilliSeconds (1)));

The following unit tests have been written to validate the implementation of DCTCP:

ECT flags should be set for SYN, SYN+ACK, ACK and data packets for DCTCP traffic

ECT flags should not be set for SYN, SYN+ACK and pure ACK packets, but should be set on data packets for ECN enabled traditional TCP flows

ECE should be set only when CE flags are received at receiver and even if sender doesn’t send CWR, receiver should not send ECE if it doesn’t receive packets with CE flags

An example program, examples/tcp/tcp-validation.cc, can be used to

experiment with DCTCP for long-running flows with different bottleneck

link bandwidth, base RTTs, and queuing disciplines. A variant of this

program has also been run using the ns-3 Direct Code Execution

environment using DCTCP from Linux kernel 4.4, and the results were

compared against ns-3 results.

An example program based on an experimental topology found in the original

DCTCP SIGCOMM paper is provided in examples/tcp/dctcp-example.cc.

This example uses a simple topology consisting of forty DCTCP senders

and receivers and two ECN-enabled switches to examine throughput,

fairness, and queue delay properties of the network.

This implementation was tested extensively against a version of DCTCP in the Linux kernel version 4.4 using the ns-3 direct code execution (DCE) environment. Some differences were noted:

Linux maintains its congestion window in segments and not bytes, and the arithmetic is not floating point, so small differences in the evolution of congestion window have been observed.

Linux uses pacing, where packets to be sent are paced out at regular intervals. However, if at any instant the number of segments that can be sent are less than two, Linux does not pace them and instead sends them back-to-back. Currently, ns-3 paces out all packets eligible to be sent in the same manner.

More information about DCTCP is available in the RFC 8257: https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc8257

BBR¶

BBR (class TcpBbr) is a congestion control algorithm that

regulates the sending rate by deriving an estimate of the bottleneck’s

available bandwidth and RTT of the path. It seeks to operate at an optimal

point where sender experiences maximum delivery rate with minimum RTT. It

creates a network model comprising maximum delivery rate with minimum RTT

observed so far, and then estimates BDP (maximum bandwidth * minimum RTT)

to control the maximum amount of inflight data. BBR controls congestion by

limiting the rate at which packets are sent. It caps the cwnd to one BDP

and paces out packets at a rate which is adjusted based on the latest estimate

of delivery rate. BBR algorithm is agnostic to packet losses and ECN marks.

pacing_gain controls the rate of sending data and cwnd_gain controls the amount of data to send.

The following is a high level overview of BBR congestion control algorithm:

- On receiving an ACK:

rtt = now - packet.sent_time update_minimum_rtt (rtt) delivery_rate = estimate_delivery_rate (packet) update_maximum_bandwidth (delivery_rate)

- After transmitting a data packet:

bdp = max_bandwidth * min_rtt if (cwnd * bdp < inflight)

return

- if (now > nextSendTime)

- {

transmit (packet) nextSendTime = now + packet.size / (pacing_gain * max_bandwidth)

}

- else

return

Schedule (nextSendTime, Send)

To enable BBR on all TCP sockets, the following configuration can be used:

Config::SetDefault ("ns3::TcpL4Protocol::SocketType", TypeIdValue (TcpBbr::GetTypeId ()));

To enable BBR on a chosen TCP socket, the following configuration can be used (note that an appropriate Node ID must be used instead of 1):

Config::Set ("$ns3::NodeListPriv/NodeList/1/$ns3::TcpL4Protocol/SocketType", TypeIdValue (TcpBbr::GetTypeId ()));

The ns-3 implementation of BBR is based on its Linux implementation. Linux 5.4 kernel implementation has been used to validate the behavior of ns-3 implementation of BBR (See below section on Validation).

In addition, the following unit tests have been written to validate the implementation of BBR in ns-3:

BBR should enable (if not already done) TCP pacing feature.

Test to validate the values of pacing_gain and cwnd_gain in different phases

of BBR.

An example program, examples/tcp/tcp-bbr-example.cc, is provided to experiment with BBR for one long running flow. This example uses a simple topology consisting of one sender, one receiver and two routers to examine congestion window, throughput and queue control. A program similar to this has been run using the Network Stack Tester (NeST) using BBR from Linux kernel 5.4, and the results were compared against ns-3 results.

More information about BBR is available in the following Internet Draft: https://tools.ietf.org/html/draft-cardwell-iccrg-bbr-congestion-control-00

More information about Delivery Rate Estimation is in the following draft: https://tools.ietf.org/html/draft-cheng-iccrg-delivery-rate-estimation-00

For an academic peer-reviewed paper on the BBR implementation in ns-3, please refer to:

Vivek Jain, Viyom Mittal and Mohit P. Tahiliani. “Design and Implementation of TCP BBR in ns-3.” In Proceedings of the 10th Workshop on ns-3, pp. 16-22. 2018. (https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3199902.3199911)

Support for Explicit Congestion Notification (ECN)¶

ECN provides end-to-end notification of network congestion without dropping packets. It uses two bits in the IP header: ECN Capable Transport (ECT bit) and Congestion Experienced (CE bit), and two bits in the TCP header: Congestion Window Reduced (CWR) and ECN Echo (ECE).

More information is available in RFC 3168: https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc3168

The following ECN states are declared in src/internet/model/tcp-socket-state.h

typedef enum

{

ECN_DISABLED = 0, //!< ECN disabled traffic

ECN_IDLE, //!< ECN is enabled but currently there is no action pertaining to ECE or CWR to be taken

ECN_CE_RCVD, //!< Last packet received had CE bit set in IP header

ECN_SENDING_ECE, //!< Receiver sends an ACK with ECE bit set in TCP header

ECN_ECE_RCVD, //!< Last ACK received had ECE bit set in TCP header

ECN_CWR_SENT //!< Sender has reduced the congestion window, and sent a packet with CWR bit set in TCP header. This is used for tracing.

} EcnStates_t;

Current implementation of ECN is based on RFC 3168 and is referred as Classic ECN.

The following enum represents the mode of ECN:

typedef enum

{

ClassicEcn, //!< ECN functionality as described in RFC 3168.

DctcpEcn, //!< ECN functionality as described in RFC 8257. Note: this mode is specific to DCTCP.

} EcnMode_t;

The following are some important ECN parameters:

// ECN parameters

EcnMode_t m_ecnMode {ClassicEcn}; //!< ECN mode

UseEcn_t m_useEcn {Off}; //!< Socket ECN capability

Enabling ECN¶

By default, support for ECN is disabled in TCP sockets. To enable, change

the value of the attribute ns3::TcpSocketBase::UseEcn to On.

Following are supported values for the same, this functionality is aligned with

Linux: https://www.kernel.org/doc/Documentation/networking/ip-sysctl.txt

typedef enum

{

Off = 0, //!< Disable

On = 1, //!< Enable

AcceptOnly = 2, //!< Enable only when the peer endpoint is ECN capable

} UseEcn_t;

For example:

Config::SetDefault ("ns3::TcpSocketBase::UseEcn", StringValue ("On"))

ECN negotiation¶

ECN capability is negotiated during the three-way TCP handshake:

Sender sends SYN + CWR + ECE

if (m_useEcn == UseEcn_t::On)

{

SendEmptyPacket (TcpHeader::SYN | TcpHeader::ECE | TcpHeader::CWR);

}

else

{

SendEmptyPacket (TcpHeader::SYN);

}

m_ecnState = ECN_DISABLED;

Receiver sends SYN + ACK + ECE

if (m_useEcn != UseEcn_t::Off && (tcpHeader.GetFlags () & (TcpHeader::CWR | TcpHeader::ECE)) == (TcpHeader::CWR | TcpHeader::ECE))

{

SendEmptyPacket (TcpHeader::SYN | TcpHeader::ACK |TcpHeader::ECE);

m_ecnState = ECN_IDLE;

}

else

{

SendEmptyPacket (TcpHeader::SYN | TcpHeader::ACK);

m_ecnState = ECN_DISABLED;

}

Sender sends ACK

if (m_useEcn != UseEcn_t::Off && (tcpHeader.GetFlags () & (TcpHeader::CWR | TcpHeader::ECE)) == (TcpHeader::ECE))

{

m_ecnState = ECN_IDLE;

}

else

{

m_ecnState = ECN_DISABLED;

}

Once the ECN-negotiation is successful, the sender sends data packets with ECT bits set in the IP header.

Note: As mentioned in Section 6.1.1 of RFC 3168, ECT bits should not be set during ECN negotiation. The ECN negotiation implemented in ns-3 follows this guideline.

ECN State Transitions¶

Initially both sender and receiver have their m_ecnState set as ECN_DISABLED

Once the ECN negotiation is successful, their states are set to ECN_IDLE

The receiver’s state changes to ECN_CE_RCVD when it receives a packet with CE bit set. The state then moves to ECN_SENDING_ECE when the receiver sends an ACK with ECE set. This state is retained until a CWR is received , following which, the state changes to ECN_IDLE.

When the sender receives an ACK with ECE bit set from receiver, its state is set as ECN_ECE_RCVD

The sender’s state changes to ECN_CWR_SENT when it sends a packet with CWR bit set. It remains in this state until an ACK with valid ECE is received (i.e., ECE is received for a packet that belongs to a new window), following which, its state changes to ECN_ECE_RCVD.

RFC 3168 compliance¶

Based on the suggestions provided in RFC 3168, the following behavior has been implemented:

Pure ACK packets should not have the ECT bit set (Section 6.1.4).

In the current implementation, the sender only sends ECT(0) in the IP header.

The sender should should reduce the congestion window only once in each window (Section 6.1.2).

The receiver should ignore the CE bits set in a packet arriving out of window (Section 6.1.5).

The sender should ignore the ECE bits set in the packet arriving out of window (Section 6.1.2).

Open issues¶

The following issues are yet to be addressed:

Retransmitted packets should not have the CWR bit set (Section 6.1.5).

Despite the congestion window size being 1 MSS, the sender should reduce its congestion window by half when it receives a packet with the ECE bit set. The sender must reset the retransmit timer on receiving the ECN-Echo packet when the congestion window is one. The sending TCP will then be able to send a new packet only when the retransmit timer expires (Section 6.1.2).

Support for separately handling the enabling of ECN on the incoming and outgoing TCP sessions (e.g. a TCP may perform ECN echoing but not set the ECT codepoints on its outbound data segments).

Support for Dynamic Pacing¶

TCP pacing refers to the sender-side practice of scheduling the transmission of a burst of eligible TCP segments across a time interval such as a TCP RTT, to avoid or reduce bursts. Historically, TCP used the natural ACK clocking mechanism to pace segments, but some network paths introduce aggregation (bursts of ACKs arriving) or ACK thinning, either of which disrupts ACK clocking. Some latency-sensitive congestion controls under development (Prague, BBR) require pacing to operate effectively.

Until recently, the state of the art in Linux was to support pacing in one of two ways:

fq/pacing with sch_fq

TCP internal pacing

The presentation by Dumazet and Cheng at IETF 88 summarizes: https://www.ietf.org/proceedings/88/slides/slides-88-tcpm-9.pdf

The first option was most often used when offloading (TSO) was enabled and when the sch_fq scheduler was used at the traffic control (qdisc) sublayer. In this case, TCP was responsible for setting the socket pacing rate, but the qdisc sublayer would enforce it. When TSO was enabled, the kernel would break a large burst into smaller chunks, with dynamic sizing based on the pacing rate, and hand off the segments to the fq qdisc for pacing.

The second option was used if sch_fq was not enabled; TCP would be responsible for internally pacing.

In 2018, Linux switched to an Early Departure Model (EDM): https://lwn.net/Articles/766564/.

TCP pacing in Linux was added in kernel 3.12, and authors chose to allow a pacing rate of 200% against the current rate, to allow probing for optimal throughput even during slow start phase. Some refinements were added in https://git.kernel.org/pub/scm/linux/kernel/git/torvalds/linux.git/commit/?id=43e122b014c9, in which Google reported that it was better to apply a different ratio (120%) in Congestion Avoidance phase. Furthermore, authors found that after cwnd reduction, it was helpful to become more conservative and switch to the conservative ratio (120%) as soon as cwnd >= ssthresh/2, as the initial ramp up (when ssthresh is infinite) still allows doubling cwnd every other RTT. Linux also does not pace the initial window (IW), typically 10 segments in practice.

Linux has also been observed to not pace if the number of eligible segments to be sent is exactly two; they will be sent back to back. If three or more, the first two are sent immediately, and additional segments are paced at the current pacing rate.

In ns-3, the model is as follows. There is no TSO/sch_fq model; only internal pacing according to current Linux policy.

Pacing may be enabled for any TCP congestion control, and a maximum pacing rate can be set. Furthermore, dynamic pacing is enabled for all TCP variants, according to the following guidelines.

Pacing of the initial window (IW) is not done by default but can be separately enabled.

Pacing of the initial slow start, after IW, is done according to the pacing rate of 200% of the current rate, to allow for window growth This pacing rate can be configured to a different value than 200%.

Pacing of congestion avoidance phase is done at a pacing rate of 120% of current rate. This can be configured to a different value than 120%.

Pacing of subsequent slow start is done according to the following heuristic. If cwnd < ssthresh/2, such as after a timeout or idle period, pace at the slow start rate (200%). Otherwise, pace at the congestion avoidance rate.

Dynamic pacing is demonstrated by the example program examples/tcp/tcp-pacing.cc.

Validation¶

The following tests are found in the src/internet/test directory. In

general, TCP tests inherit from a class called TcpGeneralTest,

which provides common operations to set up test scenarios involving TCP

objects. For more information on how to write new tests, see the

section below on Writing TCP tests.

tcp: Basic transmission of string of data from client to server

tcp-bytes-in-flight-test: TCP correctly estimates bytes in flight under loss conditions

tcp-cong-avoid-test: TCP congestion avoidance for different packet sizes

tcp-datasentcb: Check TCP’s ‘data sent’ callback

tcp-endpoint-bug2211-test: A test for an issue that was causing stack overflow

tcp-fast-retr-test: Fast Retransmit testing

tcp-header: Unit tests on the TCP header

tcp-highspeed-test: Unit tests on the HighSpeed congestion control

tcp-htcp-test: Unit tests on the H-TCP congestion control

tcp-hybla-test: Unit tests on the Hybla congestion control

tcp-vegas-test: Unit tests on the Vegas congestion control

tcp-veno-test: Unit tests on the Veno congestion control

tcp-scalable-test: Unit tests on the Scalable congestion control

tcp-bic-test: Unit tests on the BIC congestion control

tcp-yeah-test: Unit tests on the YeAH congestion control

tcp-illinois-test: Unit tests on the Illinois congestion control

tcp-ledbat-test: Unit tests on the LEDBAT congestion control

tcp-lp-test: Unit tests on the TCP-LP congestion control

tcp-dctcp-test: Unit tests on the DCTCP congestion control

tcp-bbr-test: Unit tests on the BBR congestion control

tcp-option: Unit tests on TCP options

tcp-pkts-acked-test: Unit test the number of time that PktsAcked is called

tcp-rto-test: Unit test behavior after a RTO occurs

tcp-rtt-estimation-test: Check RTT calculations, including retransmission cases

tcp-slow-start-test: Check behavior of slow start

tcp-timestamp: Unit test on the timestamp option

tcp-wscaling: Unit test on the window scaling option

tcp-zero-window-test: Unit test persist behavior for zero window conditions

tcp-close-test: Unit test on the socket closing: both receiver and sender have to close their socket when all bytes are transferred

tcp-ecn-test: Unit tests on Explicit Congestion Notification

tcp-pacing-test: Unit tests on dynamic TCP pacing rate

Several tests have dependencies outside of the internet module, so they

are located in a system test directory called src/test/ns3tcp.

ns3-tcp-loss: Check behavior of ns-3 TCP upon packet losses

ns3-tcp-no-delay: Check that ns-3 TCP Nagle’s algorithm works correctly and that it can be disabled

ns3-tcp-socket: Check that ns-3 TCP successfully transfers an application data write of various sizes

ns3-tcp-state: Check the operation of the TCP state machine for several cases

Several TCP validation test results can also be found in the wiki page describing this implementation.

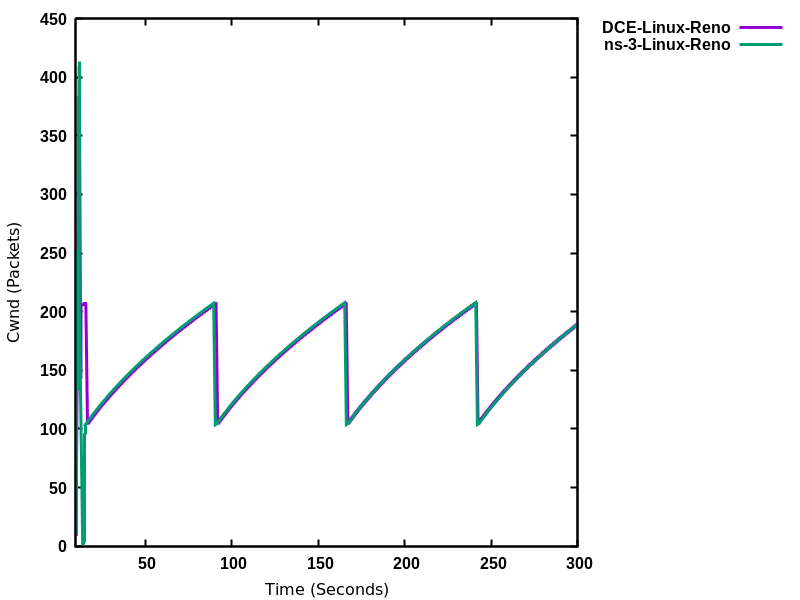

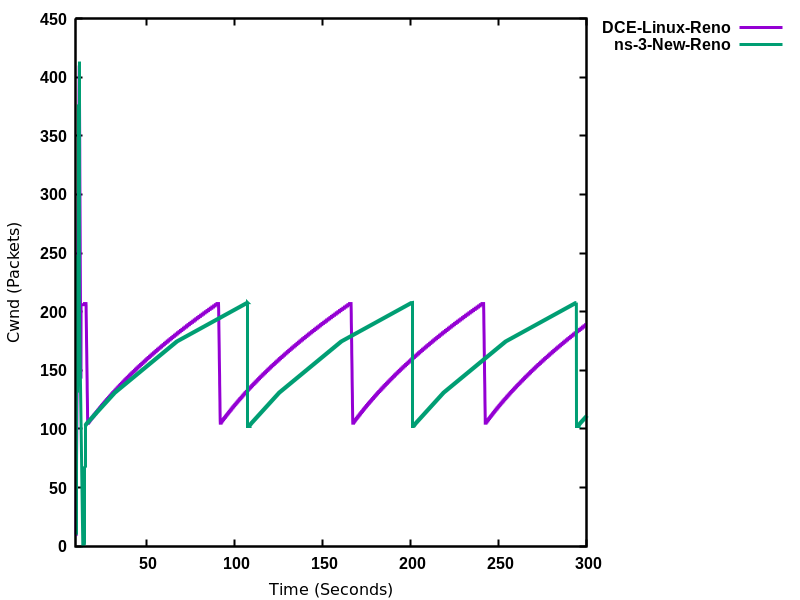

The ns-3 implementation of TCP Linux Reno was validated against the NewReno implementation of Linux kernel 4.4.0 using ns-3 Direct Code Execution (DCE). DCE is a framework which allows the users to run kernel space protocol inside ns-3 without changing the source code.

In this validation, cwnd traces of DCE Linux reno were compared to those of

ns-3 Linux Reno and NewReno for a delayed acknowledgement configuration of 1

segment (in the ns-3 implementation; Linux does not allow direct configuration

of this setting). It can be observed that cwnd traces for ns-3 Linux Reno are

closely overlapping with DCE reno, while

for ns-3 NewReno there was deviation in the congestion avoidance phase.

DCE Linux Reno vs. ns-3 Linux Reno¶

DCE Linux Reno vs. ns-3 NewReno¶

The difference in the cwnd in the early stage of this flow is because of the way cwnd is plotted. As ns-3 provides a trace source for cwnd, an ns-3 Linux Reno cwnd simple is obtained every time the cwnd value changes, whereas for DCE Linux Reno, the kernel does not have a corresponding trace source. Instead, we use the “ss” command of the Linux kernel to obtain cwnd values. The “ss” samples cwnd at an interval of 0.5 seconds.

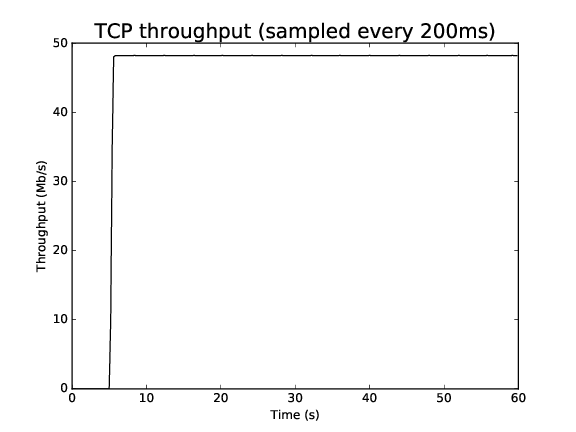

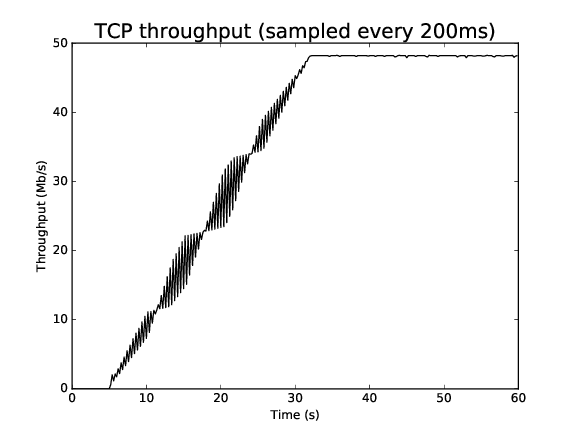

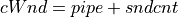

Figure DCTCP throughput for 10ms/50Mbps bottleneck, 1ms CE threshold shows a long-running file transfer using DCTCP over a 50 Mbps bottleneck (running CoDel queue disc with a 1ms CE threshold setting) with a 10 ms base RTT. The figure shows that DCTCP reaches link capacity very quickly and stays there for the duration with minimal change in throughput. In contrast, Figure DCTCP throughput for 80ms/50Mbps bottleneck, 1ms CE threshold plots the throughput for the same configuration except with an 80 ms base RTT. In this case, the DCTCP exits slow start early and takes a long time to build the flow throughput to the bottleneck link capacity. DCTCP is not intended to be used at such a large base RTT, but this figure highlights the sensitivity to RTT (and can be reproduced using the Linux implementation).

DCTCP throughput for 10ms/50Mbps bottleneck, 1ms CE threshold¶

DCTCP throughput for 80ms/50Mbps bottleneck, 1ms CE threshold¶

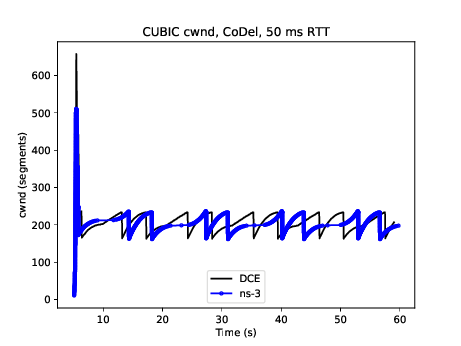

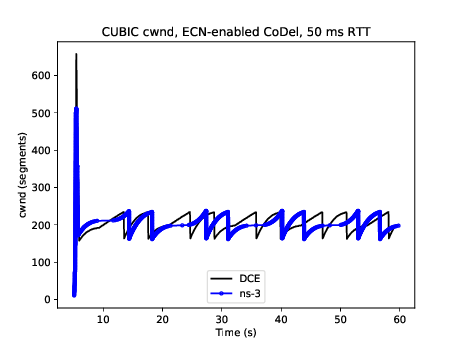

Similar to DCTCP, TCP CUBIC has been tested against the Linux kernel version 4.4 implementation. Figure CUBIC cwnd evolution for 50ms/50Mbps bottleneck, no ECN compares the congestion window evolution between ns-3 and Linux for a single flow operating over a 50 Mbps link with 50 ms base RTT and the CoDel AQM. Some differences can be observed between the peak of slow start window growth (ns-3 exits slow start earlier due to its HyStart implementation), and the window growth is a bit out-of-sync (likely due to different implementations of the algorithm), but the cubic concave/convex window pattern, and the signs of TCP CUBIC fast convergence algorithm (alternating patterns of cubic and concave window growth) can be observed. The ns-3 congestion window is maintained in bytes (unlike Linux which uses segments) but has been normalized to segments for these plots. Figure CUBIC cwnd evolution for 50ms/50Mbps bottleneck, with ECN displays the outcome of a similar scenario but with ECN enabled throughout.

CUBIC cwnd evolution for 50ms/50Mbps bottleneck, no ECN¶

CUBIC cwnd evolution for 50ms/50Mbps bottleneck, with ECN¶

TCP ECN operation is tested in the ARED and RED tests that are documented in the traffic-control module documentation.

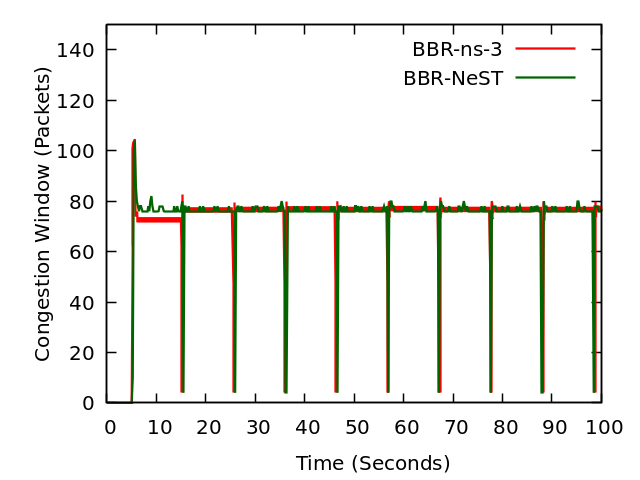

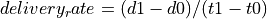

Like DCTCP and TCP CUBIC, the ns-3 implementation of TCP BBR was validated against the BBR implementation of Linux kernel 5.4 using Network Stack Tester (NeST). NeST is a python package which allows the users to emulate kernel space protocols using Linux network namespaces. Figure Congestion window evolution: ns-3 BBR vs. Linux BBR (using NeST) compares the congestion window evolution between ns-3 and Linux for a single flow operating over a 10 Mbps link with 10 ms base RTT and FIFO queue discipline.

Congestion window evolution: ns-3 BBR vs. Linux BBR (using NeST)¶

It can be observed that the congestion window traces for ns-3 BBR closely overlap with Linux BBR. The periodic drops in congestion window every 10 seconds depict the PROBE_RTT phase of the BBR algorithm. In this phase, BBR algorithm keeps the congestion window fixed to 4 segments.

The example program, examples/tcp-bbr-example.cc has been used to obtain the congestion window curve shown in Figure Congestion window evolution: ns-3 BBR vs. Linux BBR (using NeST). The detailed instructions to reproduce ns-3 plot and NeST plot can be found at: https://github.com/mohittahiliani/BBR-Validation

Writing a new congestion control algorithm¶

Writing (or porting) a congestion control algorithms from scratch (or from other systems) is a process completely separated from the internals of TcpSocketBase.

All operations that are delegated to a congestion control are contained in the class TcpCongestionOps. It mimics the structure tcp_congestion_ops of Linux, and the following operations are defined:

virtual std::string GetName () const;

virtual uint32_t GetSsThresh (Ptr<const TcpSocketState> tcb, uint32_t bytesInFlight);

virtual void IncreaseWindow (Ptr<TcpSocketState> tcb, uint32_t segmentsAcked);

virtual void PktsAcked (Ptr<TcpSocketState> tcb, uint32_t segmentsAcked,const Time& rtt);

virtual Ptr<TcpCongestionOps> Fork ();

virtual void CwndEvent (Ptr<TcpSocketState> tcb, const TcpSocketState::TcpCaEvent_t event);

The most interesting methods to write are GetSsThresh and IncreaseWindow. The latter is called when TcpSocketBase decides that it is time to increase the congestion window. Much information is available in the Transmission Control Block, and the method should increase cWnd and/or ssThresh based on the number of segments acked.

GetSsThresh is called whenever the socket needs an updated value of the slow start threshold. This happens after a loss; congestion control algorithms are then asked to lower such value, and to return it.

PktsAcked is used in case the algorithm needs timing information (such as RTT), and it is called each time an ACK is received.

CwndEvent is used in case the algorithm needs the state of socket during different congestion window event.

TCP SACK and non-SACK¶

To avoid code duplication and the effort of maintaining two different versions of the TCP core, namely RFC 6675 (TCP-SACK) and RFC 5681 (TCP congestion control), we have merged RFC 6675 in the current code base. If the receiver supports the option, the sender bases its retransmissions over the received SACK information. However, in the absence of that option, the best it can do is to follow the RFC 5681 specification (on Fast Retransmit/Recovery) and employing NewReno modifications in case of partial ACKs.

A similar concept is used in Linux with the function tcp_add_reno_sack. Our implementation resides in the TcpTxBuffer class that implements a scoreboard through two different lists of segments. TcpSocketBase actively uses the API provided by TcpTxBuffer to query the scoreboard; please refer to the Doxygen documentation (and to in-code comments) if you want to learn more about this implementation.

For an academic peer-reviewed paper on the SACK implementation in ns-3, please refer to https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=3067666.

Loss Recovery Algorithms¶

The following loss recovery algorithms are supported in ns-3 TCP. The current default (as of ns-3.32 release) is Proportional Rate Reduction (PRR), while the default for ns-3.31 and earlier was Classic Recovery.

Classic Recovery¶

Classic Recovery refers to the combination of NewReno algorithm described in RFC 6582 along with SACK based loss recovery algorithm mentioned in RFC 6675. SACK based loss recovery is used when sender and receiver support SACK options. In the case when SACK options are disabled, the NewReno modification handles the recovery.

At the start of recovery phase the congestion window is reduced diffently for NewReno and SACK based recovery. For NewReno the reduction is done as given below:

For SACK based recovery, this is done as follows:

While in the recovery phase, the congestion window is inflated by segmentSize on arrival of every ACK when NewReno is used. The congestion window is kept same when SACK based loss recovery is used.

Proportional Rate Reduction¶

Proportional Rate Reduction (PRR) is a loss recovery algorithm described in RFC 6937 and currently used in Linux. The design of PRR helps in avoiding excess window adjustments and aims to keep the congestion window as close as possible to ssThresh.

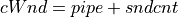

PRR updates the congestion window by comparing the values of bytesInFlight and ssThresh. If the value of bytesInFlight is greater than ssThresh, congestion window is updated as shown below:

where RecoverFS is the value of bytesInFlight at the start of recovery phase,

prrDelivered is the total bytes delivered during recovery phase,

prrOut is the total bytes sent during recovery phase and

sndcnt represents the number of bytes to be sent in response to each ACK.

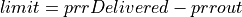

Otherwise, the congestion window is updated by either using Conservative Reduction Bound (CRB) or Slow Start Reduction Bound (SSRB) with SSRB being the default Reduction Bound. Each Reduction Bound calculates a maximum data sending limit. For CRB, the limit is calculated as shown below:

For SSRB, it is calculated as:

where DeliveredData represets the total number of bytes delivered to the

receiver as indicated by the current ACK and MSS is the maximum segment size.

After limit calculation, the cWnd is updated as given below:

More information (paper): https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2068832

More information (RFC): https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc6937

Adding a new loss recovery algorithm in ns-3¶

Writing (or porting) a loss recovery algorithms from scratch (or from other systems) is a process completely separated from the internals of TcpSocketBase.

All operations that are delegated to a loss recovery are contained in the class TcpRecoveryOps and are given below:

virtual std::string GetName () const;

virtual void EnterRecovery (Ptr<const TcpSocketState> tcb, uint32_t unAckDataCount,

bool isSackEnabled, uint32_t dupAckCount,

uint32_t bytesInFlight, uint32_t lastDeliveredBytes);

virtual void DoRecovery (Ptr<const TcpSocketState> tcb, uint32_t unAckDataCount,

bool isSackEnabled, uint32_t dupAckCount,

uint32_t bytesInFlight, uint32_t lastDeliveredBytes);

virtual void ExitRecovery (Ptr<TcpSocketState> tcb, uint32_t bytesInFlight);

virtual void UpdateBytesSent (uint32_t bytesSent);

virtual Ptr<TcpRecoveryOps> Fork ();

EnterRecovery is called when packet loss is detected and recovery is triggered. While in recovery phase, each time when an ACK arrives, DoRecovery is called which performs the necessary congestion window changes as per the recovery algorithm. ExitRecovery is called just prior to exiting recovery phase in order to perform the required congestion window ajustments. UpdateBytesSent is used to keep track of bytes sent and is called whenever a data packet is sent during recovery phase.

Delivery Rate Estimation¶

Current TCP implementation measures the approximate value of the delivery rate of inflight data based on Delivery Rate Estimation.

As high level idea, keep in mind that the algorithm keeps track of 2 variables:

delivered: Total amount of data delivered so far.

deliveredStamp: Last time delivered was updated.

When a packet is transmitted, the value of delivered (d0) and deliveredStamp (t0) is stored in its respective TcpTxItem.

When an acknowledgement comes for this packet, the value of delivered and deliveredStamp is updated to d1 and t1 in the same TcpTxItem.

After processing the acknowledgement, the rate sample is calculated and then passed to a congestion avoidance algorithm:

The implementation to estimate delivery rate is a joint work between TcpTxBuffer and TcpRateOps. For more information, please take a look at their Doxygen documentation.

The implementation follows the Internet draft (Delivery Rate Estimation): https://tools.ietf.org/html/draft-cheng-iccrg-delivery-rate-estimation-00

Current limitations¶

TcpCongestionOps interface does not contain every possible Linux operation

Writing TCP tests¶

The TCP subsystem supports automated test cases on both socket functions and congestion control algorithms. To show how to write tests for TCP, here we explain the process of creating a test case that reproduces the Bug #1571.

The bug concerns the zero window situation, which happens when the receiver cannot handle more data. In this case, it advertises a zero window, which causes the sender to pause transmission and wait for the receiver to increase the window.

The sender has a timer to periodically check the receiver’s window: however, in modern TCP implementations, when the receiver has freed a “significant” amount of data, the receiver itself sends an “active” window update, meaning that the transmission could be resumed. Nevertheless, the sender timer is still necessary because window updates can be lost.

Note

During the text, we will assume some knowledge about the general design of the TCP test infrastructure, which is explained in detail into the Doxygen documentation. As a brief summary, the strategy is to have a class that sets up a TCP connection, and that calls protected members of itself. In this way, subclasses can implement the necessary members, which will be called by the main TcpGeneralTest class when events occur. For example, after processing an ACK, the method ProcessedAck will be invoked. Subclasses interested in checking some particular things which must have happened during an ACK processing, should implement the ProcessedAck method and check the interesting values inside the method. To get a list of available methods, please check the Doxygen documentation.

We describe the writing of two test cases, covering both situations: the sender’s zero-window probing and the receiver “active” window update. Our focus will be on dealing with the reported problems, which are:

an ns-3 receiver does not send “active” window update when its receive buffer is being freed;

even if the window update is artificially crafted, the transmission does not resume.

However, other things should be checked in the test:

Persistent timer setup

Persistent timer teardown if rWnd increases

To construct the test case, one first derives from the TcpGeneralTest class:

The code is the following:

TcpZeroWindowTest::TcpZeroWindowTest (const std::string &desc)

: TcpGeneralTest (desc)

{

}

Then, one should define the general parameters for the TCP connection, which will be one-sided (one node is acting as SENDER, while the other is acting as RECEIVER):

Application packet size set to 500, and 20 packets in total (meaning a stream of 10k bytes)

Segment size for both SENDER and RECEIVER set to 500 bytes

Initial slow start threshold set to UINT32_MAX

Initial congestion window for the SENDER set to 10 segments (5000 bytes)

Congestion control: NewReno

We have also to define the link properties, because the above definition does not work for every combination of propagation delay and sender application behavior.

Link one-way propagation delay: 50 ms

Application packet generation interval: 10 ms

Application starting time: 20 s after the starting point

To define the properties of the environment (e.g. properties which should be set before the object creation, such as propagation delay) one next implements the method ConfigureEnvironment:

void

TcpZeroWindowTest::ConfigureEnvironment ()

{

TcpGeneralTest::ConfigureEnvironment ();

SetAppPktCount (20);

SetMTU (500);

SetTransmitStart (Seconds (2.0));

SetPropagationDelay (MilliSeconds (50));

}

For other properties, set after the object creation, one can use ConfigureProperties (). The difference is that some values, such as initial congestion window or initial slow start threshold, are applicable only to a single instance, not to every instance we have. Usually, methods that requires an id and a value are meant to be called inside ConfigureProperties (). Please see the Doxygen documentation for an exhaustive list of the tunable properties.

void

TcpZeroWindowTest::ConfigureProperties ()

{

TcpGeneralTest::ConfigureProperties ();

SetInitialCwnd (SENDER, 10);

}

To see the default value for the experiment, please see the implementation of both methods inside TcpGeneralTest class.

Note

If some configuration parameters are missing, add a method called “SetSomeValue” which takes as input the value only (if it is meant to be called inside ConfigureEnvironment) or the socket and the value (if it is meant to be called inside ConfigureProperties).

To define a zero-window situation, we choose (by design) to initiate the connection with a 0-byte rx buffer. This implies that the RECEIVER, in its first SYN-ACK, advertises a zero window. This can be accomplished by implementing the method CreateReceiverSocket, setting an Rx buffer value of 0 bytes (at line 6 of the following code):

1Ptr<TcpSocketMsgBase>

2TcpZeroWindowTest::CreateReceiverSocket (Ptr<Node> node)

3{

4 Ptr<TcpSocketMsgBase> socket = TcpGeneralTest::CreateReceiverSocket (node);

5

6 socket->SetAttribute("RcvBufSize", UintegerValue (0));

7 Simulator::Schedule (Seconds (10.0),

8 &TcpZeroWindowTest::IncreaseBufSize, this);

9

10 return socket;

11}

Even so, to check the active window update, we should schedule an increase of the buffer size. We do this at line 7 and 8, scheduling the function IncreaseBufSize.

void

TcpZeroWindowTest::IncreaseBufSize ()

{

SetRcvBufSize (RECEIVER, 2500);

}

Which utilizes the SetRcvBufSize method to edit the RxBuffer object of the RECEIVER. As said before, check the Doxygen documentation for class TcpGeneralTest to be aware of the various possibilities that it offers.

Note

By design, we choose to maintain a close relationship between TcpSocketBase and TcpGeneralTest: they are connected by a friendship relation. Since friendship is not passed through inheritance, if one discovers that one needs to access or to modify a private (or protected) member of TcpSocketBase, one can do so by adding a method in the class TcpGeneralSocket. An example of such method is SetRcvBufSize, which allows TcpGeneralSocket subclasses to forcefully set the RxBuffer size.

void

TcpGeneralTest::SetRcvBufSize (SocketWho who, uint32_t size)

{

if (who == SENDER)

{

m_senderSocket->SetRcvBufSize (size);

}

else if (who == RECEIVER)

{

m_receiverSocket->SetRcvBufSize (size);

}

else

{

NS_FATAL_ERROR ("Not defined");

}

}

Next, we can start to follow the TCP connection:

At time 0.0 s the connection is opened sender side, with a SYN packet sent from SENDER to RECEIVER

At time 0.05 s the RECEIVER gets the SYN and replies with a SYN-ACK

At time 0.10 s the SENDER gets the SYN-ACK and replies with a SYN.

While the general structure is defined, and the connection is started, we need to define a way to check the rWnd field on the segments. To this aim, we can implement the methods Rx and Tx in the TcpGeneralTest subclass, checking each time the actions of the RECEIVER and the SENDER. These methods are defined in TcpGeneralTest, and they are attached to the Rx and Tx traces in the TcpSocketBase. One should write small tests for every detail that one wants to ensure during the connection (it will prevent the test from changing over the time, and it ensures that the behavior will stay consistent through releases). We start by ensuring that the first SYN-ACK has 0 as advertised window size:

void

TcpZeroWindowTest::Tx(const Ptr<const Packet> p, const TcpHeader &h, SocketWho who)

{

...

else if (who == RECEIVER)

{

NS_LOG_INFO ("\tRECEIVER TX " << h << " size " << p->GetSize());

if (h.GetFlags () & TcpHeader::SYN)

{

NS_TEST_ASSERT_MSG_EQ (h.GetWindowSize(), 0,

"RECEIVER window size is not 0 in the SYN-ACK");

}

}

....

}

Pratically, we are checking that every SYN packet sent by the RECEIVER has the advertised window set to 0. The same thing is done also by checking, in the Rx method, that each SYN received by SENDER has the advertised window set to 0. Thanks to the log subsystem, we can print what is happening through messages. If we run the experiment, enabling the logging, we can see the following:

./ns3 shell